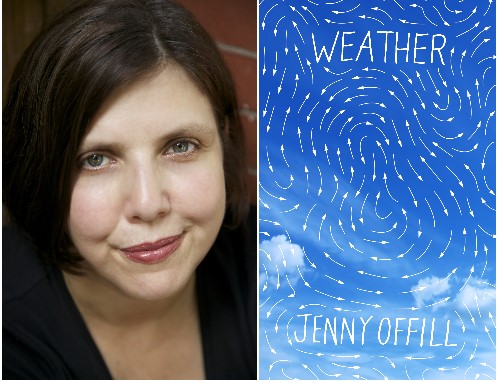

On March 16th we were meant to host novelist Jenny Offill here at Mr B’s, to chat about her incredibly moving, intelligent and funny new novel ‘Weather’. Due to the COVID-19 crisis, Jenny was unable to make it across the pond this time. Although we’re absolutely gutted we couldn’t sit in the shop and chat in person, we’re very excited to share a brief Q&A between Jenny and our Jess, about the present moment, other people’s realities and the many things that hope can mean.

In ‘Weather’ the narrator Lizzie takes up a job replying to emails for her former tutor who now hosts a podcast called ‘Hell and High Water’. Lizzie’s story is therefore interspersed with and echoed by a multitude of voices, each expressing their dread, anger, desperation and resilience with regards to the future. Inspired by the novel, we asked those of you who had tickets for Jenny’s event to write to us, finishing the following sentences:

‘To hope is to…..’

It’s the year 2030 and….’

As you read the interview, you’ll find some of the answers dotted around. We do hope you enjoy it and love ‘Weather’ as much as we do. To purchase a copy of the book visit our web shop HERE.

Jess: Very few of us could have imagined that we’d be communicating in this way a few months ago – trying to keep creativity, support and livelihoods of all kinds afloat in the midst of a pandemic. Something we started doing recently at home, as a way to keep ourselves going and to stay engaged with climate activism, is to tell each other something we’re grateful for every day. Could you tell us one thing you’re particularly grateful for with regards to the writing and publication of ‘Weather’?

Jenny: I am grateful for the people I met and read about while researching it. Many of them were accidental activists but all of them had moved away from denial or fatalism (which is its own kind of denial) and into a more expansive emotional state. And I feel incredibly lucky and a little guilty that it came out before all this. It’s such a hard time to have a new book came out.

To hope is to be vulnerable.

It’s the year 2030 and the world’s biggest ever international tree-planting project is almost complete.

Jess: Both Lizzie in ‘Weather’ and the narrator in ‘Dept. of Speculation’ constantly move between a strong pull to safety, tribe and intimacy and an urgent awareness of the precipice that lies beyond the familiar – be it a world crisis or the unravelling of a marriage. It’s a very vulnerable, and I’d say essential, place to stick around in as much as we can. What’s the first time you can remember exploring this kind of unravelling?

Jenny: I’ve always been interested in other people’s troubles while also, of course, being caught up in my own. When I lived in NYC, I found it almost impossible not be drawn into all the small dramas around me. There is such much emotion in just one subway car. Sometimes it felt overwhelming. There’s this line in a Gary Lutz story that I love. Someone asked a guy if he’s “involved with anyone” and he says “everyone, I’m involved with everyone.” Writing fiction gives me a place to corral all that interest and worry.

To hope is to plant a garden.

Jess: At one point Lizzie quotes a climate scientist talking about trying to decide on where to move in order to be as safe as possible from the effects of climate collapse. I think I watched the same documentary, by the way! Has your feeling of what it means to feel safe changed in the time since you started writing ‘Weather’?

Jenny: Yes, very much so. I feel safer now than I did when I began the novel. When I started out, I was still in the mode of looking for an answer, trying to find out where I should move or what I should do. By the end, I had become a convert to the idea of collective action. I joined climate groups including Extinction Rebellion and began to come out of my silo of dread. It was hard and also kind of exhilarating to be part of something bigger than myself. One of the many difficult things about our current pandemic crisis is it thwarts many of the way we comfort each other in times of disaster, what Rebecca Solnit so wisely deems disaster solidarity. It is hard not to offer my house to people fleeing the city or to make food and drop it off for affected neighbors. But everyone is having to find new ways of community. I just taught my first class by Zoom the other day and was surprised how heartening it was to see all my students faces even if they were in little boxes.

It’s the year 2030 and the Great Barrier Reef has survived another decade.

Jess: The climate scientist Kate Marvel wrote that ‘we need courage, not hope’ but I keep thinking that this all depends on what you mean by hope. That’s why I’ve asked our readers to give their own definitions. What does hope mean to Lizzie?

Jenny: I think hope sometimes involves an idea of rescue and we need to move away from that. I used to have a quote over my desk from Isak Dinesen. It said “Work a little each day without hope and without despair”. This is, of course, impossible as I tend to swing back and forth between these two poles on a daily basis. But when it comes to addressing the climate emergency this idea makes sense to me and it is something I tried to cultivate in Lizzie by the end of the novel. Camus called it ‘activism fatalism” and wrote about it in The Plague. The doctor in it says that what will stop the plague is decency not heroicism and this seems very true to me. He goes on to describe active fatalism as akin to a person fumbling his way in the dark, trying to do what is right, not knowing if it will work or not. In both the climate crisis and this current one, all we have for sure is our own moral compasses. Decency, kindness, fairness, these are the ideas that must guide our actions as we work for the common good.

To hope is to believe that there better ways of doing things, and that, regardless of whether or not it’s possible for those ways to be realised, it’s worthwhile putting ourselves in service to them

Jess: What, to you, is the opposite of anxiety?

Jenny: My anxiety takes the form of dread. For me, the only antidote for dread is collective action.

To hope is to live.

It’s the year 2030 and we haven’t given up.

It’s the year 2030 and we are in renewal.

Jess: Going back to ‘Weather’, it is very much about the future, without going beyond our present moment. Was it a challenge at all to stay here, without veering into fictional speculation about the future in the narrative itself?

Jenny: I knew that I didn’t want to write a post-apocalyptic novel about climate change. That territory has been well-covered. I am usually interested (perhaps to a fault) at trying to capture how it feels to be alive at a particular moment in time. ‘Weather’ was an attempt to chart that especially the movement between different registers of concern, some global, some domestic.

But I did do something I’ve never done before in this novel; I jumped a little bit into the future at the end because there is a scene where Lizzie votes again and this is meant to take place during the November 2020 presidential election. Afterward, she mills around outside the building surrounded by strangers and neighbors remembering something her friend told her. He said people who are lost often walk past their own search parties. That search and rescue teams sometimes have to tackle them because they are in such a daze of lostness and hopelessness.

I love this idea that we might not recognize our own search party made up of helpful strangers. It speaks to this idea of the power of collective action and it is the reason Lizzie begins to say things such as “What if we went for a walk? If we walked out into the streets?” This current disaster, the pandemic, has exposed how interconnected we all our, how actions in one part of the world have effects on the other. Climate change also reveals this interconnectedness for better or for ill. When the environmentalist Bill McKibben is asked by someone “What can I do as an individual about climate change?” he always gives the same answer. ‘Don’t act as an individual, act as part of a community.” This is a difficult directive for someone like me, a long time avoider of groups, but I see the truth in it now. I so admire what someone like Rob Hopkins has done with the Transition Towns movement. I feel like it gives a template of how to create a future that is more community-based and thus, by all measures, more resilient in times of trouble. And best of all this particular movement manages to show the fun of what it might mean to live more slowly, more locally, less precariously.

To hope is to love one another, despite what the neo-darwinists claim.

Jess: There are so many things I want to ask you, many of them about what kind of stories we need at the moment, and I really hope there will be an opportunity for that at a later date. For now, thank you so much for taking the time to share your thoughts. Both my partner and I, as climate activists and writers, as well as several colleagues in the shop, have found such gems of clarity and so much to hold close in ‘Weather’. Thank you for writing it.

Jenny: Thank you for these terrific question. I was so disappointed not to get to come to Mr. B’s Emporium of Reading Delights (best bookstore name ever!) I very much hope I can come visit in the future and talk to you more.

It’s the year 2030 and the right decisions were made in 2020.